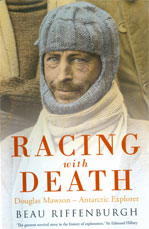

Racing with Death tells the breathtaking story of Douglas Mawson’s Antarctic expeditions, in which he more than once narrowly escaped with his life. His solitary struggle against the odds on his Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) was described by Sir Edmund Hillary as ‘the greatest survival story in the history of exploration.’

Racing with Death tells the breathtaking story of Douglas Mawson’s Antarctic expeditions, in which he more than once narrowly escaped with his life. His solitary struggle against the odds on his Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) was described by Sir Edmund Hillary as ‘the greatest survival story in the history of exploration.’

Mawson had been a key member of Ernest Shackleton’s 1907–09 Nimrod Expedition, when he was part of the first team to reach the region of the South Magnetic Pole. In 1911 his own AAE set off for the Great White South, establishing base at Cape Denison, which proved to be the windiest place on Earth. Mawson sent out numerous sledging parties to explore different areas. But when first one and then the other of the two members of his own party died, he was left to struggle the hundreds of miles back to base on his own. Despite incredible hardships, he made it, only to find that the rescue ship had sailed away but hours before, leaving him to face another year in the Antarctic.

Mawson later led a two-year expedition that explored hundreds of miles of unknown Antarctic coastline. Scientifically and geographically speaking, his expeditions were groundbreaking, and established Australia as a key player in the Antarctic. Mawson himself, who had complex relationships with both Scott and Shackleton, was changed utterly by his struggles in that harshest of environments, and his story is a fascinating insight into the human psyche under extreme duress.

Amazon.co.ukHardcoverWaterstones

Scott Polar Research InstituteAmazon.comUS Hardcover

Extract

He hung limply in space, a thin Alpine rope slowly spinning him round over a black, bottomless chasm. He was mentally exhausted, physically drained, and virtually frozen from the snow and ice that had seeped inside his clothing. And he was totally alone, some eighty miles from the closest living person.

It would only take a moment, thought Douglas Mawson, the leader of the grandly named Australasian Antarctic Expedition, and then he would never again feel the pain, the anguish, the torment of recent weeks. All he needed to do was slip from his harness, and he could be free at last; he would simply fall through the air and thence into a deep, merciful, everlasting sleep.

Other thoughts crowded his mind: of his fiancée waiting patiently for him far away, of the ‘secrets of eternity’ that he might soon discover, and of the terrible events that had brought him to such a forlorn place. Everything had gone so wrong, beginning with that day a month before when, in a previously unexplored region of the Antarctic, one of his two companions had disappeared forever down a deep crevasse with their best sledge dogs, most of their food, their tent, and many other necessities for existing in one of the harshest climates on Earth. For three weeks, Mawson and his remaining colleague, the Swiss ski expert Xavier Mertz, had engaged in a frantic, resolute race against time, desperately trying to cover the 300 miles back to their coastal base. They were soon wracked by exposure, dehydration, and starvation. Even eating the remaining dogs – which became too weak to pull the sledge – did not provide them with enough sustenance, and they were soon confronted by a mysterious condition that saw their skin slough off, their sores not heal, and their will-power overwhelmed by lethargy. Finally, the ailing Mertz rejected the option of continuing, and Mawson was forced to play nursemaid – until Mertz’s death had ended his suffering.

But that placed Mawson in an even more appalling situation. There was inadequate food, even for one, the sledge was too heavy for a single man to haul, and the weather daily threatened to trap him in his tent at a time when lack of action could prove fatal. Moreover, he was unable to move without pain, writing about his condition: ‘My whole body is apparently rotting from want of proper nourishment – frost-bitten fingertips festering, mucous membrane of nose gone, saliva glands of mouth refusing duty, skin coming off whole body.’

But Mawson was made of stern stuff, even by the demanding standards of the Antarctic explorers of the time, and after cutting the sledge in two with a small knife, he struggled on for more than a week. He had no choice but to keep moving, and one morning as he blundered blindly along in a weak light that made it difficult to see, he was suddenly pulled up with a jerk, and found himself dangling fourteen feet down a crevasse. The sledge continued to slide towards the gaping hole. ‘So this is the end,’ he said to himself, expecting it to crash through the ice and carry him to the depths below. But it did not happen. Miraculously, the sledge ground to a halt near the edge.

His prospects were daunting, nevertheless. The crevasse was six feet wide, and he could not reach either side. Above him, he could see that the rope had sawed into an overhanging lid of ice, which would make it difficult to draw himself onto the surface, should he even get that far. The more he looked, the farther it seemed, particularly in his weakened condition. In addition, his fingers and hands were frost- damaged, and, being gloveless, were fast losing sensation. His torso was also numb since, due to the exertion of pulling the sledge, he had taken off much of his clothing and left the rest pulled open – so it had filled with snow and ice when he crashed through the covering of the crevasse.

But, he thought, Providence had given him a last chance, and so, with a superhuman effort, he reached along the rope and drew himself up, and then again, and again, each time expecting the change in position to pull the sledge over the edge, but finally reaching a knot in the rope, which gave him just enough of a hold to rest. After some time, he repeated the process, the small knots holding out the promise of success, and of life. Finally, seemingly after an age, he reached the overhanging snow lid and managed to crawl out on its surface, almost to safety, when it suddenly burst into pieces, propelling him back down again.

Now truly chilled, with his strength almost gone, he swung back and forth, convinced that his life would soon be over. Above, the surface might have been miles away, while below, the black depths beckoned, promising to end his misery and toil. Undoing his harness was easy enough, and would allow him to end this torture. Mawson’s hands were slowly drawn to the harness, and to eternity.