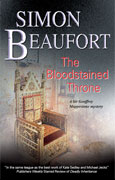

The Seventh Sir Geoffrey Mappestone Mystery

The Seventh Sir Geoffrey Mappestone Mystery

Murder, betrayal, and open rebellion …

When the former Crusader knight Geoffrey Mappestone and his friend Roger of Durham try to slip out of England to the Holy Land, a ferocious storm destroys the ship they are on and casts them ashore not far from where William the Conqueror had landed decades before.

The two knights are unwillingly thrust into the company of other shipwrecked passengers. These include two women who may have committed murder, a mysterious merchant who apparently pushed his closest friend overboard, and a seemingly crazed man alleging he is the son of former Saxon King Harold – and therefore the legitimate claimant to the English throne.

As Geoffrey tries to evade the unwelcome attentions of the more dangerous members of the group, he meets yet others claiming the throne and is drawn deeper into a plot that aims to overthrow King Henry and return England to Saxon rule.

Amazon.co.ukHardcoverKindle EditionWaterstoneseBook

Amazon.comUS HardcoverUS Kindle Edition

Extract

The track twisted through several copses, then reached land that had been cleared for fields. Directly ahead were more trees with a hamlet nestling among them, comprising four or five pretty houses and an attractive church. A short distance away was an unusual building, which looked as though it had just been hit by a snowstorm. Geoffrey regarded it curiously.

‘Ah! Werlinges,’ said Harold in satisfaction. He pointed at the building that had caught Geoffrey’s attention. ‘And that is one of its salt-houses.’

Geoffrey frowned. The village was strangely deserted at a time when men should have been tending fields or livestock. And someone certainly should have been in the salt-house. Salt was an expensive commodity and usually well guarded. Meanwhile, the door to the chapel was ajar, moving slightly in the breeze. The dog sniffed, then growled, a deep and long rumble that made up Geoffrey’s mind.

‘Stop,’ he said softly. ‘There is something wrong.’

‘Wrong?’ demanded Magnus. His voice was loud and rang off the nearest houses, and them seemed even emptier. ‘What do you mean? Are you afraid? Like father, like son?’

The scorn in his voice was more galling than his words, and Roger bristled on his friend’s behalf. But Geoffrey was more concerned with the village. Bale gripped a long hunting knife and started to move forward, but Geoffrey stopped him. He had not survived three gruelling years on the Crusade by being reckless, and all his senses clamoured that something was badly amiss.

‘I do not want to go through this place,’ he said. ‘We will walk around it.’

‘But what about the horses that Harold arranged to be waiting?’ demanded Magnus angrily. ‘You cannot expect kings to arrive at La Batailge on foot, like common serfs.’

‘Then we will wait here,’ said Roger. ‘Go and collect your beasts.’

‘Alone?’ asked Magnus, immediately uneasy. ‘When you think it is dangerous?’

‘It is all right,’ said Harold in relief. ‘I can see the horses in the field over there. I asked Wennec the priest to hire me good ones, and he has! I confess I was concerned he might renege.’

‘Why?’ asked Geoffrey, scanning the trees. There was no birdsong again, and the entire area was eerily silent. ‘Is he dishonest? Or just loath to have anything to do with rebellion?’

‘Werlinges has always expressed a preference for Normans,’ admitted Harold. ‘I imagine that was what prompted the Bastard to spare it.’

‘So why ask its priest to find your horses?’ asked Geoffrey suspiciously. ‘Why not go elsewhere for help?’

‘Harold has just told you why,’ said Magnus impatiently. ‘All the other settlements were laid to waste. Werlinges is the only village available, so he had no choice but to approach Wennec.’

‘Then that is even more reason to leave,’ said Geoffrey. ‘Surely you can sense something oddly awry here? There are no people, but there are the horses, flaunted in an open field. It is a trap.’

‘Nonsense,’ declared Magnus. ‘Everyone left because of the storm. But enough of this blathering – go and fetch the nags at once.’

Neither knights nor squires moved. Then, casually, Roger drew his sword, testing the keenness of its blade by running the ball of his thumb along it. Geoffrey stood next to him, his senses on full alert.

‘If you want the horses, get them,’ said Roger to the Saxons. ‘If not, we shall be on our way.’

‘All right,’ said Harold, moving forward. ‘We shall show you Saxon courage.’

‘I will come with you,’ said Brother Lucian. ‘I do not fancy walking all the way to La Batailge, so I will borrow a pony if there is one to be had.’

‘Do not make your selection before your monarch has picked one for himself,’ ordered Magnus, hurrying after him.

He broke into a trot. So did Lucian, until they both made an unseemly dash towards the field, like children afraid of losing out on treats. Juhel chortled at the spectacle, although Geoffrey was too uneasy to think there was anything remotely humorous in it.

‘Perhaps I had better ensure our noble king does not lose out to a “Benedictine”,’ said the parchmenter. ‘Because I suspect he is incapable of selecting a good horse.’

Geoffrey regarded him sharply. ‘You are sceptical of Lucian’s vocation, too?’ he asked.

Juhel gave one of his unreadable smiles. ‘Well, I have never seen him pray. Of course, it may just be youthful exuberance that makes him forget his vows.’

‘He is certainly not bound to chastity,’ said Roger. ‘I am sure he and Edith lay together on the ship. And that gold pectoral cross he wore speaks volumes about his adherence to poverty, too. If he is a monk, then he is not a very obedient one.’

‘His worldliness makes him an inappropriate choice for such a long, lonely mission,’ said Juhel. ‘So either Bishop de Villula had to choose him for reasons we will probably never know, or Lucian is using a religious habit to disguise his true identity.’

‘And why might that be?’ asked Geoffrey, regarding Juhel warily, aware that these were probably observations that had been fermenting for some time. But why was the man so interested in his fellow passengers?

‘Lord knows,’ said Juhel. ‘An escape from an unhappy marriage, perhaps? He was the first to abandon ship, and, although he claims he took nothing, I saw him towing a small bundle. And I am sure it did not contain a psalter.’

He ambled away, leaving Geoffrey confused and uncertain. Was Juhel casting aspersions on Lucian to deflect suspicion from himself? Or was he just a man who liked to watch the foibles of others?

‘This village has a smell,’ said Bale, his whisper hot on Geoffrey’s ear. The knight eased away from his squire, not liking the hulking figure quite so close. ‘A metallic smell, and one I know well.’

‘Something to do with the salt-house?’

‘Blood,’ drooled Bale. ‘I smell blood.’

‘You do not,’ said Geoffrey firmly. ‘But we are leaving as soon as Harold has his horses, so go and make sure the road north is clear. Take Ulfrith with you. And be careful.’

‘You were right: there is something wrong about this place,’ said Roger as Bale slipped away. ‘And Bale might be right: I think I can smell blood, too. The sooner we are gone, the better.’

Geoffrey’s reply was drowned out by a monstrous shriek, and he saw men running from the woods wielding weapons. At their head was the pirate Donan, his face a savage grimace of hatred. In the distance, Geoffrey was aware of the Saxons, Juhel and Lucian swivelling around in alarm. They scattered immediately. Magnus ran awkwardly, all knees and flailing arms, while Juhel tipped himself forward and trotted like an overweight bull. Harold and Lucian were less ungainly, and Geoffrey did not think he had ever seen a faster sprinter than the monk.

‘Death to thieves and saboteurs,’ Donan howled, sword whirling. ‘Now you will pay!’